Charting the weblog's rise to global significance, from the primordial soup of the early net to the big league platforms of the mid to late noughties.

In terms of the public attention it’s managed to grab, blogging has arguably upstaged some of the most powerful forms of entertainment on Earth. But its beginnings were humble, to the point that most of the tech industry considered it a lost cause. How things changed.

In this post, we'll take a journey back through time, to revisit and analyse the birth, tepid ascendancy and explosion of the blog, in the days before it was robbed of its role by social media, and was reinvented as a commercially-run content-marketing machine. In the days before building a successful blog required a business development manager, a multi-skilled creative team, full-stack coders, a planning division and an outreach budget. At one time, creating a blog post was no more demanding than writing a Mastodon post. No title. Just a date for a heading and a small block of top-of-the-head text.

That haphazard jumble of personal opinion, speculation and me-me-me-ing seemed an unlikely seller as the 'nineties drew to a close. So when the blogging backwater first emerged from the joyfully chaotic backdrop of the early Web, the tech industry suspected it would quickly burn out. Few startups wanted to take a punt on it.

After eight months in the public domain, Pyra's flagship blogging tool, Blogger, had managed to attract just 3,000 sign-ups. That's an average of 12.5 new users per day.

Their concern – that the supply of content would dwarf the demand and spread irreparable disillusionment across the genre – was well-founded.

Most early blog content was of interest only to the blogger themselves. With no obvious mass audience, and user-interfaces nestling well into the territory of cumbersome, early Blogging resources such as Blogger, grokSoup and Manila were far from overnight sensations. In fact, in the year 2000, after eight months in the public domain, Pyra's flagship blogging tool, Blogger, had managed to attract just 3,000 sign-ups. That's an average of 12.5 new users per day. Worldwide. Your local book club could probably have beaten that by knocking on doors.

If you want your blog posts to contain any sort of formatting or links to other pages, you need to know some HTML. - Original Blogger owner Pyra, 1999

So what changed to make blogging the explosive trend it had become by 2005? Who invented blogging? What was the difference between a blog and a website? And why did that difference come to matter so much? Let's find out…

PRIMORDIAL SOUP

If you took a wander around cyberspace in 1997, you’d find a world in which, homepages aside, websites were routinely built like digital sculptures. Intended to remain the same forever. Not just in terms of content – their designs were typically baked into the page-code too. Each individual page resided in its own self-sufficient HTML file. Static. Final.

Unusually by today's standards, the 1990s sites' visual designs often varied from one page to the next. Not by calculated intention, but because it was simply too laborious a task to individually update a site's old pages each time the admin came up with a new and better design. New pages would get the new design, but there was no single-step way to inject it into the old pages, so the old pages retained their original styling.

And it wasn't just the colours and layouts that could change. Late '90s website pages could alternate between fixed and fluid width, with fixed pages manifesting different width specifications from one to the next. Levels of GIF animation could also vary wildly, as admins tried to find a sweet spot between eyecatching and annoying.

The timing of Google’s February 2003 purchase of Blogger perfectly illustrates the point in history at which weblogging rose into the mainstream.

Meanwhile, navigation systems only offered backward motion. For example, the sidebar on a December 1997 page could contain a link to a November 1997 page, but not to a January 1998 page, because the January 1998 page had not existed when the December 1997 page was finalised and published. Linking to future content would only become a convenient proposition with the arrival of dynamic loading.

The static builds of the 1990s placed huge constraints on highly active publishers. But not everyone was resigned to staying still…

THE INVENTORS OF BLOGGING

Few commentators would be brave enough to pronounce one individual the inventor of blogging. There was certainly a blogging scene in place well before the word "blog" (b.1999), or even the word "weblog" (b.1997), hit the landscape. But it was an evolutionary progression - not a single action of innovation.

Dave Winer is one of the most widely-credited early bloggers, having begun his association with feed-based publishing in 1996. Winer was undeniably a major force in popularising what would come to be known as the "blog". And he also drove forth knowledge of its technical foundations, courtesy of his popular outlet Scripting News and a first-generation blogging service called Manila. But Winer's conversion to dynamic publishing was significantly predated by blog-like output from people like Randy Cassingham.

Cassingham launched his This is True feed as early as 1994. And given that - outside of educational facilities - the Web barely existed before that, we have to place Cassingham's earliest work pretty close to the dawn of leisure-based online publishing.

This is True, as it originally existed, would be much more accurately described as a newsletter than a blog. Arguably a primitive version of what Substack is today. But in the mid 1990s, email distribution was just the logical way to maintain the kind of persistently updating feed that would later characterise blogs. Indeed, Cassingham subsequently released his 1990s content in blog archive format without any need for modification, so there’s a very strong argument that he was an early blogger.

Sadly, only isolated facets of the early Internet were preserved, so we'll probably never be able to chart the roots of blogging in detail. What we do know is that the movers and shakers in early blogging circles were referenced as "independent journalists", and their main rivals were actual news media organisations, who, online at least, initially struggled to compete with them.

Subsequently, as we're now all too well aware, Silicon Valley decided that for some unknown reason the "professional" media had an automatic entitlement to Web traffic, however much zero-effort cow-poop they wrote. At that point, all the elitism of the pre-Internet world was neatly and immovably restored.

TECHNOLOGICAL BACKGROUND

Before 1999, despite the signs of demand for blogging tools, even highly active publishers were broadly still building pages as static files using graphical generators such as Adobe PageMill or Microsoft Frontpage. Others created pages using Netscape Navigator’s HTML editor, or else simply coded the pages manually by typing raw HTML into an empty file. Dynamic, server-side scripting did already exist, but as with responsive Web design, it was considered dicey to use it in the early years of the Web - albeit for different reasons. The reasons prohibiting dynamic loading for website content in the '90s included:

- Processing and bandwidth limitations.

- Low general awareness of the benefits.

- Expectations and convention - for example, a search engine or directory might expect a page to remain exactly the same once published, and eject pages with evolving content as unstable or unpredictable.

But the desires would soon outstrip the reluctances, and dynamic loading techniques began to creep into the picture.

Using scripting languages such as Cold Fusion, PHP or ASP, it was possible to interface a web page with a server-resident database. This enabled the page to accept live input from a perpetually updating store of content, preventing published matter from becoming “stranded” in time, and giving rise to the dynamic feed that came to define a blog.

The basic concept was very simple. Use placeholder variables to represent the content on the page, and then replace them with actual content from a database as the page was called by a visitor's browser.

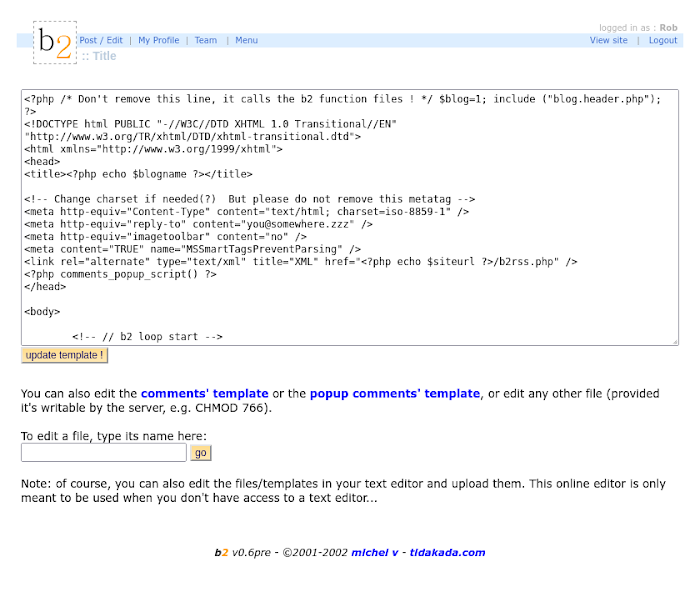

The most famous of the 1990s blogging platforms did not, however, produce dynamic output from birth…

Introduced in 1999, Blogger was built around ASP, Java and XML, but it still produced static pages as its final, published output. It later stored drafts to a database, then published a template-guided HTML file to its eventual online location via FTP. Later still (circa 2006), it would switch to dynamic loading for all blog pages. But in the beginning, Blogger generated classic HTML files.

Trivia Hit

On Blogger, it's still possible to access the old, pre-2006 templating system - now known as the First Generation Classic system and selectable from the dropdown above the themes menu. Activating First Gen Classic will dig up an otherwise hidden theme from that pre-2006 era. And in that theme, you'll be able to see the giveaway trait of static conversion: the sidebars only list links to previous posts - nothing more recent. All of Blogger's output pages are dynamically loaded today, but that tell-tale static compromise still survives in the old theme templates.

So when, in June 2001, Michel Valdrighi's b2 software launched, offering fully dynamic, direct-from-database output, it became THE hot blogging resource of the early 2000s. A true stepping stone between the static, immutable culture of the early web, and the database-driven feed culture of Web 2.0.

The concept of pumping user-content directly from databases into browser windows has been the absolute defining factor of the modern Web. Without it, the algorithmically-driven, personalised timeline systems of social media simply couldn't exist.

With b2 equipping bloggers for the future, technology was ready for the blogging explosion. But there were quite a few hurdles to jump first…

THE DARK AGE

In early 2001, the market for blogging tools had looked bleak. Much supply, not so much demand. At that low-point, Prya (Blogger) CEO Evan Williams had been about as close to dire straits as a Silicon Valley tech boss could get without actually going bust. Having lost all his staff due to financial difficulty, during spring ’01 Williams struck a deal with Dan Bricklin’s web publishing company Trellix, giving Trellix rights to integrate Blogger into its packages in exchange for a desperately needed financial injection.

Along with Williams’ resolve, the intervention kept Blogger afloat long enough for the market to catch up. By the August of 2002 Bricklin was reporting a significant boom in demand for blogging tools – citing the most noticeable rise in interest as having occurred between the spring and summer of that year.

What increased the public's appetite? In Bricklin's opinion (and that linked post is a brilliant encapsulation of the turning point in the blog's fortunes)…

The general public is starting to realize that [blogging] is a great means for individuals, organizations, and businesses to communicate and share timely information and interact with friends, associates, and customers.

He also referenced the increasing press coverage of blogging, and mentioned the compatibility of a blogging system with emerging uses, such as change logs and, prophetically, statuses.

People were finally grasping the fundamental difference between a blog and a website, and realising how that important difference - dynamic loading - could bring new dimensions to their online communication.

BLOGGING GOES MAINSTREAM

After the sharp upturn in interest for blogging through 2002, Google stepped in with a bid for Pyra’s Blogger publishing system and its accompanying Blog*Spot hosting service, which concluded with an outright purchase of both offerings in February 2003.

In the run up to the purchase, Blogger had seen big advancements in user-friendliness and scope, albeit primarily for users who paid for one of the platform's upgrade packages.

For example, by late 2002, paying Blogger users could avail themselves of:

- Automatic RSS.

- A title entry box in the post editor.

- Photo uploading (required two separate upgrades).

- Post templating (so the page design would not have to be coded separately for each post).

- Static, off-blog pages.

- Ad-free hosting when using the Blog*Spot platform.

- Visitor stats for Blog*Spot.

- Password encryption so traffic sniffers couldn't hack your Blog*Spot on a whim.

Looking at the list, it's pretty startling how basic, not to mention vulnerable, blogging still was for non-paying users.

But with Google bracing up to shift all of Blogger's premium features into the free tier, it appeared that Blogger would go forward to dominate the world of mainstream blogging. I mean, with the pre-evil Google behind it, how could it not? Especially given that the future of b2 - technically the better software - had been cast into some doubt at exactly the point when Google's Blogger purchase was going through…

RESUSCITATING B2

In the world of online publishing, the b2 system was conceptually advanced, dynamically loading blog posts directly from a MySQL database, via a PHP back end, to render continuously evolving and fully-updatable HTML in the browser window.

But by January 2003, b2's creator and lead developer Michel Valdrighi had opened up a widening gap in his online activity. Not having shown a traceable presence since a forum login at the end of November 2002, Michel V was considered to have abandoned his b2 project. There are hints in a conversation from early spring '03 that he'd been disillusioned, and taking into account the work involved in maintaining Free Software, versus its low potential for reward, it's easy to see how that would happen.

But inevitably, given the potential of b2 in a world now waking up to the appeal of blogging, there was someone more than ready to step into Michel V's shoes.

It's become a commonly held view that b2 was saved by a teenage American blogger, musician and code tinkerer by the name of Matthew Mullenweg, alongside the pro UK developer Mike Little, who in a now famous exchange on Mullenweg's blog, offered to assist him.

But b2's survival was really built into its licencing model. Released on the GNU General Public License, b2 was forever open for any developer(s) to copy the code to their own workbase and continue its upkeep on their own terms - a move known as forking. The original project's lead dev did not need to quit in order for that to happen. And the speed with which Mullenweg announced an intention to fork the b2 project - less than two calendar months after Valdrighi's last login and before many others in the community even noticed he'd gone - suggested that he may have been planning to fork the project anyway.

My own belief is that there would have been a WordPress in any event. But whatever the truth, b2 did need to be spearheaded by someone with Mullenweg's tech-boss mentality if it was to challenge a corporate-owned platform like Blogger.

THE DESIGN THEME RACE

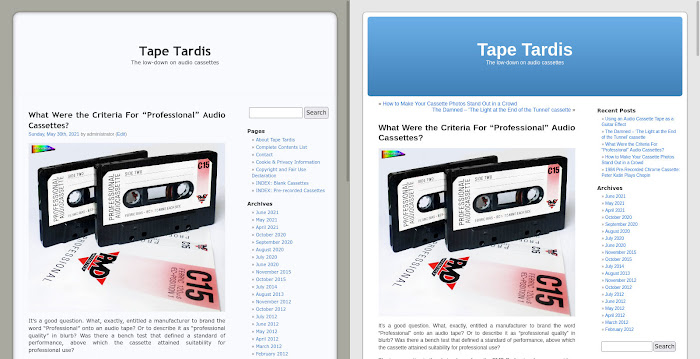

Matt Mullenweg launched his fork of b2 in May 2003, under the brand name WordPress, with a notably fast and simple installation process that would help further cement the reputation already built by b2.

But the droolsome range of design themes for which WordPress eventually became famous were conspicuously absent at the outset. In 2003 and 2004, WordPress distributions were built around a single template referenced as "Default WordPress".

The first release of the "Default Wordpress" styling was written by Matt Mullenweg himself, and its stylesheet contained just 171 lines, including the opening comment and all spaces.

It was debatable whether this original default constituted a theme at all. It could perhaps be better described as a boilerplate or bootstrap, and the accompanying comment presented it in that light…

This is just a basic layout, with only the bare minimum defined. Please tweak this and make it your own. :)

At the time, bloggers were still expected to code their own design templates, but if the mass public were to have visually-striking blogs, this would have to change. It soon did…

Zen Garden CSS guru Dave Shea bolstered the visuals of the original WordPress default template, to produce a theme that would ultimately become known as WordPress Classic. Shea's revised default template - which again incorporated work by Mullenweg - debuted with WordPress 0.72 in autumn '03.

But knowing how partial the public were to impactive visuals, WordPress went out of its way to stimulate production of open source design themes. Although initially, such luxuries only came as separately downloadable accessories.

Google had marched farther down the road, and in February 2004, Blogger integrated a wide range of professional, pre-fabricated design themes, courtesy of several top designers. Aesthetics ace Douglas Bowman had developed a number of wicked themes for Blogger within the batch, but one particularly notable contribution - Rounders - used a transparent masking GIF technique to produce rounded corners on the page elements. At the time, rounded corners could not be produced purely with CSS styling code, and the new, softened look garnered much kudos.

As Blogger users were showered in aesthetic enticements, WordPress needed a response.

And as if by magic, it simultaneously summoned one. Also in Feb '04, contributing WordPress developer Alex King organised a design competition that brought forth a raft of CSS stylesheets and made them available as accessory downloads. Some of the designs produced for this amateur contest were later introduced to the WordPress.com theme collection.

A year later, King launched another competition to coincide with the landmark intro of WordPress 1.5. WordPress 1.5 had a full theme-switcher built in, and thus its capacity for design changes was not confined to mere stylesheet replacements with accompanying images. Accordingly, this second contest sought full theme templates rather than just stylesheets. Entries were many, and once again, some designs were later integrated into the WordPress.com theme collection.

KUBRICK - AN ICON OF THE ASCENDANT BLOGOSPHERE

But in between those two design contests came the WordPress theme that would come to symbolise the blogging explosion: Kubrick.

The design for Kubrick owed much to an ongoing realm of design experiments on its developer's own blog - Michael Heilemann's Binary Bonsai.

The Kubrick story can be said to have started at the birth of WordPress itself, in spring 2003. Heilemann was an immediate adopter of the original WordPress 0.7, and from there, the look of Binary Bonsai quickly evolved away from its 'websitey' appearance, toward customised versions of the early WP default blog templates. Heilemann's customisations prompted interest from his readers, which ultimately drove the creation of Kubrick.

Kubrick was low-key announced by Heilemann on Wednesday 14th July 2004, in this blog update, entitled Templating WordPress…

Tonight is going to be spent tying up the loose ends for a free WordPress template I've been meaning to put out for months and months now.

Who'd have imagined that the above sentence would herald the single most famous blog theme of the 2000s?

Well, it did. Heilemann's period of procrastication had come to an end, and at this point he pitched into a rapid and dynamic pre-launch drive. With WP boss Matt Mullenweg watching the surrounding buzz like a hawk, Heilemann began sending out beta copies within a couple of days, and then set up to release the theme at the end of the month. In the event, public release was delayed by one day, and Kubrick was launched as an independent accessory for WordPress on 1st August 2004.

Announced to a wider audience by Mullenweg on its launch day, the slick new template garnered instant applause, with downloads going crazy, and the amassing crowd suggesting that Kubrick should be bundled with the next version of WordPress. It became the WordPress Default theme from version 1.5, and remained so for five years, eventually being deposed by Twenty Ten, in er… 2010.

ARTIFICIAL STIMULUS

Despite the increasing writer-focus (as opposed to geek-focus) of blogging utilities, there was still a problem. A problem whose conqueror would ultimately win the battle of the blog providers.

It had already been shown that the public needed to be offered more than free tools to sign up to a blogging service en masse. They needed free hosting too. With the pre-evil Google at the helm, Blogger had cracked this nut, and WordPress caught up in 2005 with the launch of WordPress.com. But there was something else. The public also needed something which most people don't have, and never will have… An audience.

From the off, this had been a problem for blogging startups. There was no significant audience for random people's opinions or top-of-the-head thoughts. Unless you're famous, no one cares that you're decorating your house or taking your car in for an MOT. They don't care if you bought a coffee, or whether you enjoyed it, or how much of a crush you have on your neighbour. They never will. And since almost all traditional blog content fell into this category, anyone hoping to run a booming blogging platform needed a solution.

A solution that Web 2.0 would conveniently provide.

Web 2.0 came in with the concept of artificial stimulus. A series of functions that would turn an online platform into a transactional exchange. 'Like' buttons, 'Follow' features, comment boxes, etc. Blogs already had commenting, but on a centralised platform it was easier to drive reciprocal use of it. Add in the other transactional features, and suddenly there's an audience.

It's all fake, obviously. Bob comments on Alice's blog because Alice has traffic, and Bob might get some of that traffic by commenting. And he doesn't get his cut of the traffic because his comment matters per se. He gets it because other bloggers now know that Bob comments on blogs, and he might comment on their blogs. But he has to notice them first, so they have to comment on his blog. So Bob gets some of Alice's traffic. And so it goes on.

The genius of Web 2.0 is that human ego can never quite bring itself to acknowledge that all those likes, comments, follows, etc, are purely transactional bids for attention. Even today, after twenty years of it, we think every round of digital applause is real - provided it's directed at us, and not someone else, that is.

And it was through deft harnessing of transactional ego-massage that WordPress.com managed to create an audience for any type of content, of any standard. It felt like a community. Warm. Like home. And it had the best wallpaper.

Blogger lost the battle of the blogging platforms because it never achieved that same sense of community. WordPress won, and went on to become the Web's leading content management system by an overwhelming margin. But WordPress.com had barely crossed the finish line before its own impending nemesis - Big Social - was shaping up as a rather more formidable opponent.