"In the long run, there's only so much mileage in these brands persistently directing the public's thoughts towards what is actually, in truth, their products' worst attribute."

The privacy bandwagon is in town, and the cart is pretty crowded as it rounds the corner onto High Street. As each jostling brand throws its surface-scrubbed privacy parcels out to the roadside gathering with gleeful abandon, open hands grab at the shower of generous gifts.

The public broadly accepts cybertech's privacy claims at face value, and this has created a digital Gold Rush, in which all manner of companies wave brightly-decorated incognito masks at Google's userbase, in the hope of enticing a lucrative mass exodus. But when Google's users jump across into this wonderful new world of incognito, it slowly dawns on them that Google has made the jump too - in an incognito mask of its own.

TELL ME SWEET LITTLE LIES...

Do any of the jostling brands really care whether their privacy parcels contain any privacy? Perhaps a better question would be: do we care? If we don't care, why should they? And we don't care. We want to believe that privacy is something we can download in a little parcel, because then life is easy and we don't have to do any thinking. When brands are telling us what we want to hear, we won't question it - especially when the product is free. Free as in beer, I mean - not, necessarily, free as in freedom.

So we've reached a point at which cybertech companies know they can seduce us with constant use of the trigger-word "privacy", regardless of its validity. And sometimes, the word is anything but valid.

A SHORT DETOUR

For example, new kid on the block Neeva describes itself as a "private search engine". But behind the fanfare, Neeva necessarily locks users into the greatest freedom/privacy-destructor of all… An identity-verified login.

Neeva doesn't serve ads. DuckDuckGo does. And that's Neeva's sleight of hand.

Hey, we don't serve ads, so we must be more private.

But there's no inherent connection at all between ads and privacy. Strip away Neeva's marketing and DuckDuckGo is infinitely more private. Why? Because you don't have to provide your identity to use it, and then sit locked into an inescapable spy-box while it creates an ID-rubber-stamped behaviour dossier.

Neeva offers zero privacy above the legal minimum. ZERO. It necessarily knows who you are! It admits to collecting data. It admits sending search queries to Microsoft. It tacitly admits to selling "anonymised" data. And the punchine is that it expects users to pay $4.95 a month for the privilege of using what must be the least private "private search engine" in the world.

This is an encapsulation of what anti-surveillance knowledgeables are describing as "privacy-washing". Marketing with the word "private" because it's known to be phenomenally effective, rather than because it's true.

But the Neeva factoid also gives us a neat route into the world of Vivaldi browser, since Vivaldi has recently ushered Neeva into its official search options in the US. More worryingly, Vivaldi has validated Neeva's spray of privacy-wash by describing the product as "privacy-friendly". So are Neeva and Vivaldi sharing a bottle of privacy-shampoo? Let's find out…

VIVALDI BROWSER ON MERIT

We should bear in mind that Vivaldi's software and services are free (again, as in beer), and that free software and services offered by any centralised, substantially-investing enterprise are going to turn the user into a product to a greater or lesser extent. Much as Vivaldi would love us to believe otherwise, that's the reality.

But this is a browser analysis, specifically assessing whether Vivaldi's marketing claim of privacy-focus is fair. There's no incentive or bias either way. It's a genuine opinion piece.

INSTALLATION

Before I start, I should mention that I tested Vivaldi 4.3 (built on Chromium 94) in both Bodhi Linux 6.0 and Q4OS 3.14. It's an easy installation after you've downloaded the .deb file. Just open the Terminal in your Downloads folder (or wherever else the .deb file ended up after download) and type or paste…

sudo dpkg -i vivaldi-stable*.deb; sudo apt -f install

A few seconds of jiggery-pokery and the browser pops up in your Internet Applications, ready to run. Same drill for both Debian- and Ubuntu-based Linux distros.

OUT OF THE BOX...

We expect to have to change a lot of settings in order for any browser to achieve a good standard of privacy, and Vivaldi is no exception to that. Cookies and JavaScript are enabled, as are "services" such as Phishing and malware protection, and DNS to help resolve navigation errors (alias DNS to help send your browsing history to Google). These defaults and others are problematic in privacy terms for different reasons.

Cookies permit aggressive tracking, and inexplicably (given its privacy stance), in my installations Vivaldi allowed the use of third-party cookies by default. Third-party cookies are the system used by cockroach ad-barons to tail you round the web.

Vivaldi's browser settings bill this pre-selected option as applying to non-private windows only, but most people will be using non-private windows, most of the time. With third-party cookies enabled you will be tracked heavily across domains. It's a ridiculous default for a browser claiming to respect privacy.

First-party cookies would also be disabled by real privacy advocates, then selectively allowed per domain as necessary. But because blocking first-party cookies will kill logins, it's considered fair even for privacy-respecting browsers to allow first-party cookies by default. So first-party cookies would have been acceptable. Third party - no way.

JavaScript powers the bulk of the internet's hardcore spyware. But because a high proportion of the web has deliberately been engineered not to work without it, once again, private browsers are normally excused a default of active JavaScript. Vivaldi comes with JavaScript switched on, and does allow it to be disabled and selectively managed. However, the means to do this is not available in Vivaldi's own settings pane. You need to access Chromium's base settings. To do this, type chrome:settings into the URL bar, then head for Privacy and security > Site Settings.

Having to essentially hack your way into the JavaScript control is not what I'd categorise under "good privacy standards". Especially given that surveillance giants (including Facebook) are turning to JavaScript tracking schemes as more traditional practices steadily lose their effectiveness.

Options like Phishing and malware protection and DNS to help resolve navigation errors look, at first glance, to be in users' interests. However, they don't appear in the Security section of the settings. They appear in the Privacy section. Which hints at the fact that these background "services" are really just there to send data to third party companies - usually Google.

In the case of the DNS resolver, you're basically letting Google monitor your browsing history in exchange for very occasional re-railing in the event that a URL falls off the track. It's really not a good deal, and neither is it, in my view, an acceptable default on any browser claiming a privacy focus. That said, this default is very much the rule, not the exception - even among "privacy" browsers.

THE URL BAR

Vivaldi rapidly claws back some lost points with its URL bar options. Whilst it comes with Bing set as default search for the regular browsing window and DuckDuckGo for the private window, both of my installations defaulted to non-aggressive operation. The default search engines (which you can change) only ran searches when I typed in text and told them to search. They didn't chat in the background as I typed, on the pretext of "offering search suggestions". They can be set to offer search suggestions if you really want that, but it wasn't the default. I would describe this implementation as 100% above board. No tricks.

Furthermore, Vivaldi allows users to disable URL bar searching altogether in the regular settings. With many other browsers - including Firefox and Chromium - you have to go deep into the developer params or trick the mechanism by setting up a fake default search engine. Knowing how browsers tend to roll with regard to the URL bar, I half expected Vivaldi's Off switch not to work. It does work. Switch it off, and it's off.

TRACKERS IN THE TRASH

Vivaldi 4.3 wins another raft of points in its integration of native protection against known trackers. You can easily switch this on or off in the Privacy settings. And I can assure you that unlike similar native options on some other browsers, this one does work, and it works well. It would be nice to be able to see what's being blocked within the browser itself, but I've done A/B tests with the feature on and off, and my firewall's reports show that it's not just a piece of furniture. It blocks known trackers, whilst letting through vital third party content. Whether it blocks all known trackers is another question.

There's also an ad-blocker, which I didn't test. Quite enough of the web has been driven behind paywalls by ad-blocking as it is. My stance is that if sites can serve ads without additional surveillance routines or other underhanded mechanisms connected to them, we should consider those ads part of the page. If they can't, the tracker-blocker blocks the ads, so there's no need for specific ad-blocking.

I couldn't determine how the block lists are updated, who updates them, or whether this can be done separately from the main browser update process. Software providers in general need to be far less opaque about how things work. Inform within the user interface.

This might be a good time to mention that Vivaldi has opposed certain privacy-busting Google initiatives native to Chromium and Chrome - the latest of which is the so-called Idle Detection API. Slammed in the Fediverse and well beyond, Idle Detection affords data-desperate websites yet another way to spy on their users - even outside of their own domain networks. Wisely, Vivaldi has disengaged this needless peep-hole. So whilst Chrome 94 has it slyly enabled by default, the Vivaldi release built on top of it does not.

THE NITTY-GRITTY

With a wide range of settings adjusted, and the peripheral stuff like Translation, Safebrowsing and Spell Check switched off, I opened up an internet connection with no page loaded. This is where things began to go back downhill again…

Vivaldi wants to phone home. Vivaldi wants to update (calm down, I've only just downloaded it!), Vivaldi wants to talk to Google. Vivaldi wants to talk to Google again. No, Vivaldi really, REALLY wants to talk to Google, RIGHT NOW!!!...

This is what happens when browser users are cut out of the update consent loop, and the products decide they're going to ping their update domains whether anyone likes it or not. The Google domains Vivaldi was desperately trying to talk to appeared to be part of the update regime. They were…

update.googleapis.com

redirector.gvt1.com

dl.google.com

Why Vivaldi needs to communicate with Google for updates I don't know, but short of firewalling the domains, I couldn't find a way to stop the connections. More apparently mandatory calls to Vivaldi attempted to resolve the following domains…

mimir.vivaldi.com

update.vivaldi.com

downloads.vivaldi.com

At a guess, I'd say the first of these domains collects the user stats, and the other two are for updates. Vivaldi have admitted tagging every browser user with a unique ID for the purpose of collecting stats, and that info must be sent during at least one of the above calls.

That's pretty straightforwardly bad form for a brand marketing on privacy, although most browser providers (including Mozilla and Brave) do it, and Vivaldi can at least be credited with publicly admitting and discussing it on their own blog.

Forced updates, or unpreventable connections to update domains, are an even greater problem - especially when, once again, you have Big Brother on the other end of the line.

"Privacy" brands need to consider why it is that people are so concerned about hidden, unauthorised connections specifically to Google. Google has to all intents and purposes become unavoidable in cyberspace, and that is deeply disturbing.

Everything you do, no matter where you go, has Google sitting in the background with a pair of binoculars. Google pays for tickets to watch you in every last corner of the web. The issue is, YOU don't get a single penny of the £billions it spends on tickets. And if you chuck Big Brother out of the venue he sneaks straight back in through a hidden trap door. There are so many of these trap doors built into the average browser, that it is purely and simply impossible for anyone who is not a privacy-tech expert to eliminate Google from the picture. Impossible.

That's why people get so angry when brands like Brave and Vivaldi grandstand about privacy, and then all but guarantee some sort of connection to the single biggest surveillance machine on the internet.

People wonder why I post on a Google service when I'm so bothered about the extent of its control over the digital landscape. But if I used any other blogging platform, visitors would still get tracked by Google. Whether on the sites themselves via analytics, content or font delivery routines, or via their browsers' background services, or both. Even the tracker-blocker uBlock Origin lets through certain Google dependencies. This company is UNAVOIDABLE. So why even try to make it look like you're giving people an escape? At least on a Google service, everyone knows what's what, and no one is under any illusions. And I don't claim to be running a "private blog".

Software has become progressively more invasive, more bloated and more controlling, consistently, for the past ten years. And it's reasonable on that basis for at least some people to regard updates as a bad thing. I don't wanna hear all the bullshit about "security". It's not about security. It's never been about security. It's about constantly finding new means to surveil people in ways they haven't yet learned to detect.

So if browser providers do care about privacy, as opposed to just the increase in userbase that the P-word brings them, they need to use clear language, provide information about what each function actually does and WHO does it, and obtain proper, informed consent. If they want to update to a new version, with new code, they need to fully explain what's changed - what they're putting in; what they're taking away. And they need to ask us before making those changes.

The reason they don't do this, is because if they actually showed us, in plain language and with full transparency, what their updates were about to do, too large a proportion of their userbase would refuse. There's a reason why updates evolved from fully optional, via nags, and via click-walled off switches, to a full-on forced regime. And let's face it - the reason is not that users wanted them. Eth Tech brands need to stop with the gaslighting on this. Stop trying to pretend everyone loves having no control over their computers.

MORE HEADACHES IN BODHI LINUX

The installation I made to Bodhi Linux differed from the installation I made to Q4OS. In Q4OS (Debian-based) Vivaldi 4.3 functioned normally and with pretty watertight privacy standards once I'd adjusted LOTS of settings and firewalled off its unauthorised connections.

However, in Bodhi (Ubuntu-based), the exact same browser exhibited very different behaviour.

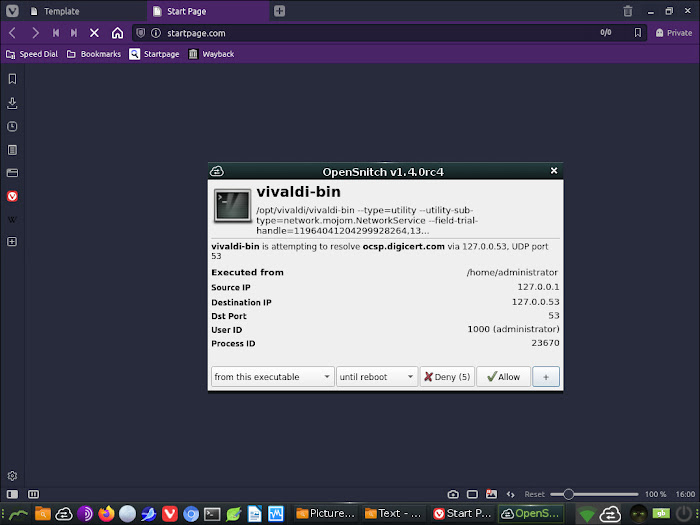

It appeared to be using a zero-tolerance OCSP/CRL regime to check the certificate for every encrypted web page before allowing the visit. The browser would connect me directly to a data-mining certificate authority before I could visit any encrypted page. No bypass. I hunted for a solution for a good while and could not find one.

Since most of the web is now HTTPS-only, there was no way to visit the majority of sites or platforms without telling Digicert, or Godaddy, or Sectigo, or whichever other advertiser-schmoozing surveillance-cockroach happens to be the relevant certificate authority for the site in question.

I've raised the issue of this encryption racket and its surveillance implications on the blog before, and the problem is far-reaching. But this was the most inescapably intrusive implementation of certificate checking I've seen, and none of my other browsers do this in Bodhi. Whether it's down to a Chromium Field Trial setting I don't know, and I don't really care. Vivaldi are the ones asserting that this browser has good privacy standards, and it's their responsibility to make sure it does have good privacy standards.

LOOSE ENDS

There were other, more minor privacy itches in Vivaldi 4.3. I don't like the closed tabs feature, which retains page views even when you have your history set to clear at the end of a session, and requires you to keep clearing data manually. Private Browsing mode surmounts this, but you can't use Private Browsing for everything.

I don't like that when you delete bookmarks they don't actually get wiped. They go into a "Deleted" section. Hey Vivaldi, if I can still see it, that's not called deletion. A "Deleted" bucket that contains stuff I can still see is a comedy sketch - not a feature on a privacy browser.

SUMMING UP

There are far worse "privacy solutions" than Vivaldi on the scene, and with its user-customisable visuals, Vivaldi is the best looking browser around. It has a good feel, the layout's great, you don't need to install extensions… And if you're someone who needs the browser's range of additional features, direct rivals quickly drop away.

It's sad that there were data leaks and inappropriate defaults completely destroying something which could so easily be an elevated shining light in the world of browsers. I hate Brave's business model, and Vivaldi presents a far more pleasant environment. Those of us who were fans of Opera browser in its pre-Chromium days can appreciate the sense of style and added value that also characterises Vivaldi - a product led by the same CEO.

With Firefox on the down and down, and Vivaldi showing clear intentions to dislodge the old Mozilla beast from its former Linux strongholds, it's a great time for the Icelandic contender to hit its peak. But for me, Vivaldi 4.3 proved unusable within a solid privacy framework in Bodhi Linux - the cert-checking fiasco really was that bad.

At the other end of the scale, Vivaldi 4.3 got a lot of things right, and for now, I will keep the non-certificate-crazed incarnation online in Q4OS, albeit with updates and Google connections firewalled.

There is, of course, the fact that we wouldn't even be judging Vivaldi on its privacy if the brand didn't repeat the P-word in every other sentence. We didn't judge Opera on its privacy. We judged it on its performance, its lightness, its rendering, its feature-packed goodie-box, and its "pretty face". That was a different time, in which browsing standards were generally much lower, and a good product like Opera really stood out. Remember how awful Internet Explorer was in comparison?

But today, nearly everyone builds off Chromium, so there's no longer any significant difference in things like performance and rendering. That's one of the reasons Firefox has lost so much of its userbase in recent times. Its performance is inferior to that of Chromium - in part due to Google's ever-increasing control of web standards. And that means Firefox's performance is also inferior to that of Chrome, Vivaldi, Brave, Slimjet, and every other rival built off the Chromium base.

We now have a glut of browsers with the same engine, all trying to distinguish themselves based purely on tailored marketing strategies. It's vastly more about what they say than what they do. So I can see why the privacy thing has become such a major battleground.

But in some ways it's counter-productive, because it constantly draws attention to something most of us didn't even think about in the heyday of Opera. We're scrutinising the surveillance potential of these products at a depth we never would have done in 2011. And as the brands fixate our attention more and more on privacy, that's only going to get worse.

One can't help feeling that some of these "privacy" brands are writing out their own execution warrants. We're buying it for now. But in the long run, there's only so much mileage in them persistently directing the public's thoughts towards what is actually, in truth, their products' worst attribute. Privacy is not what they're good at. Out of the box, browser privacy is almost invariably awful. What happens when that hard fact goes mainstream? Chromium-based browsers urgently need to find new ways to distinguish themselves from Chrome, because Joe and Jane public won't be leaving those empty privacy parcels unopened for much longer.